Laura El-Tantawy’s most recent work, “A Star in the Sea,” the latest in her string of highly artful self-published book productions, raises for me a most interesting question. One thing that makes serious photobooks unique is that we’re looking at both photography and bookmaking, and where the line of emphasis between the two can shift from book to book. My own preference is for more focus on great photographs (The Americans, Eggleston’s Guide), less on the artistic expression in the book’s actual construction, which of course is not to say I don’t like a well-made, innovative book. It’s just that as a rule, I want the quality of the images, and their flow and significance in the book, to be predominant.

The last work I looked at here, Jason Eskenazi’s “Black Sea Trilogy,” is a good example: books of strong, moving photographs, arranged with deep meaning, but also in a creative, unusual format (three books that all fit together, creative chapter making, the photos in each book surrounded by a different and meaningful frame) that suits both the photos themselves and the overall sweep of Eskenazi’s artistic ambitions.

Pushing this mix of strong photos and innovative layout even further is El-Tantawy’s magnificent first book, “In the Shadow of the Pyramids”—an almost perfect photobook. The photos are strong, from the family snapshots at the front of the book—it’s hard to think of a more personal photobook maker than El-Tantawy; much more on this to come—to the perfect “build” that opens the photographer’s own shots. “Build” … I tell my fiction students to work on that all the time, draw us in, up the complicity and intensity, then deliver a payoff. So in “In the Shadow of the Pyramids,” El-Tantawy’s first seven photos grow in size page by page until we hit her eighth, which is full bleed (the size of most of the rest of the shots in the book, interspersed by occasional photos from her family album, and finally a quiet diminuendo at the end, the photos tapering down in size to mimic the opening). And what a great, telling shot that first full-bleed one is: rich in vibrant and slightly off-kilter color, as many of El-Tantawy’s photos are, this one swirls and sweeps with undergarments flapping in a breeze over a jaundiced yellow Cairo skyline—a beautiful photo in its own right.

“In the Shadow of the Pyramids” was mostly shot during the Arab Spring uprising in Cairo. El-Tantawy was born in England to Egyptian parents, and has lived in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the U.S., but was hugely moved by the political movement nearly a decade ago. As she puts it in one of a few word essays in the book, “When people took to the streets on January 25, 2011, I had to be among them. It was a moment when my past, present and future came together as never before…. In Tahrir Square I found myself again.”

The photos in the book, mostly from Tahrir Square, capture political force, and counterforce; excessive passions, rising hopes, outrage, and even one striking portrait of a woman with eyes uplifted, hands held together in prayer; powerful resolve and flowing tears; battles engaged and wounds dressed; and overall as powerful a photographic examination of a moment of dire political upheaval as I can think of, the rival of two other impressionistic protest books, Shomei Tomatsu’s “Okinawa” and “What Is 10/21,” from a Japanese student collective, yet little else.

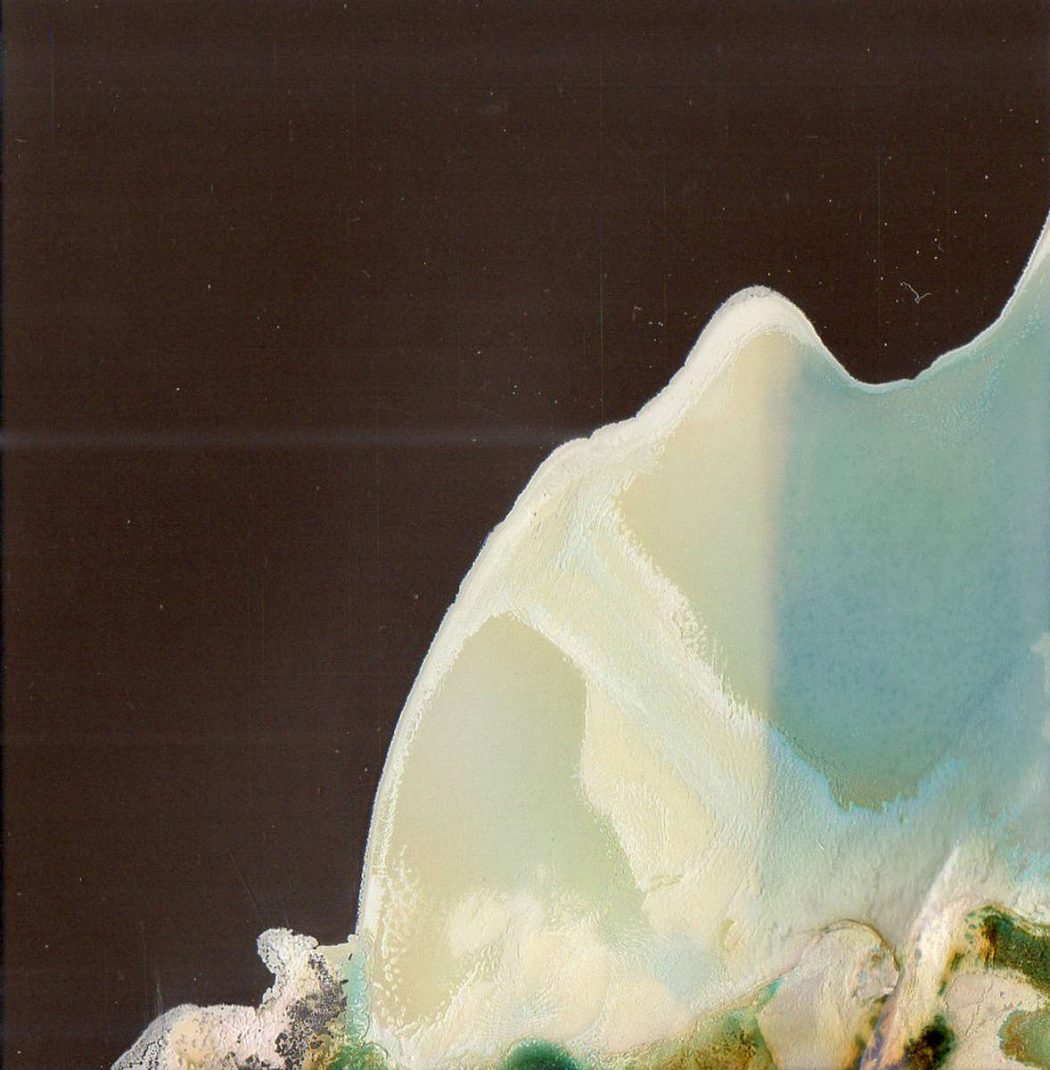

Much of the power for me of “In the Shadow of the Pyramids” comes from El-Tantawy’s photographic style. Call it impressionistic, as I just did, or an exuberantly colorful updating of the Provoke era’s are-bure-boke, (grainy/rough, blurry, out-of-focus), or the artist’s own understanding that you don’t need highly realistic documentary photos to best capture true moments. This is a book of rampant color, yellows, oranges, and most of all reds. I can barely find a shot in the book in which a person’s normal skin tones prevail; most often they are furious eruptions of the colors noted above, the hues of passion and violence. (The 2011 rebellion successfully removed Hosni Mubarak from the presidency, but at least dozens of protestors were shot and killed by police, and Arab Spring soon turned to Arab Winter.)

One advantage I’ve found from photographing into thick, emotionally engaged crowds is that you can easily get up very close to people, and El-Tantawy does that here. She catches faces from mere inches away, all pure expressions of palpable emotion. Chances are any citizen has only a single life opportunity, if that, to actually realize political change by protest, and El-Tantawy does a great job of expressing through these close-ups just what the moment means to the Egyptians involved. Simply, we’re there with her.

And the shots that are mostly washes of color, near abstractions? Or the ones with bodies dark silhouettes before the stunning colors? The best photographs are not what you want to see but what the camera itself actually observes. So the blur, the abstraction, the shadows and shapes and bursts of unreal color … they’re all the truth of the moment, as captured by the camera, which of course is simply a tool of El-Tantawy’s powerful vision.

The book itself is extremely well made, from its rough cloth cover with an image of two children on a camel (a family photo?), a dark, elongated shadow-man imposed upon it like an inkblot. The cloth cover makes the photo inevitably, and suitably, very grainy. Most of the pages in the book are folded-over sheets, perhaps to allow the colors to be richer on a page backed only by the white side of the paper. This unusual paper choice also gives the whole book a greater weight and thickness, which suits its importance. The folded paper also makes the book, looked at from its paper-side edge, an intriguing striation of colors, bounded by white sheets of the early and later pages, which are not full bleed. The overall effect of “In the Shadow of the Pyramids” is to embed interest and effect (and affect) in every aspect of the book, and in every moment of reading it.

I didn’t set out here to review “In the Shadow of the Pyramids,” a book now four years old (and long out of print, alas), but it’s a book well worth talking about, and one I’m sure will be discussed for years to come. So this here becomes Part 1 of my two-part piece on El-Tantawy’s books. The next will be on her two major photobooks after “In the Shadow of the Pyramids,” “Beyond Here Is Nothing” and the brand-new “A Star in the Sea.” Those books … well, that question I raised at the opening of where the line between photography and book falls, and how it can be moved, that’s the question I’ll dive deep into in Part 2. As El-Tantawy puts it, “Trying not to repeat myself, every project deserves its own visual language. What that language will be and how I will consistently apply it across a body of work so it feels cohesive is always a challenge.”

A challenge, indeed. For both the photobook maker and for us, her audience. El-Tantawy has not repeated herself, that’s for sure (though in all her books, her palette remains somewhat the same). She’s moved further and further in the direction of photobook as pure art object.

And as we’ll see, she’s done that most intriguingly.

A selection of books by Laura El-Tantawy can be purchased here.

Robert Dunn is a writer, photographer, and teacher. His latest novel is Savage Joy, inspired by his first years in NYC and working at The New Yorker magazine. His photobooks OWS, Angel Parade, Carnival of Souls, and New York Street are in the permanent collection of the libraries of the Museum of Modern Art and the International Center of Photograph (more info on Dunn’s own photobooks here; prints of his work can be ordered here, follow his instagram here). Dunn also teaches a course called “Writing the Photobook” at the New School University in New York City.

Images below from In The Shadow of the Pyramids by Laura El-Tantawy.

1 Comment