I’ve come to not like the term street photography. I feel in a way it’s time is over; it’s what Robert Frank and William Klein and Garry Winogrand and Joel Meyerowitz did so well fifty or sixty years back (put nicely in historical perspective by the book Bystander: A History of Street Photography, by Meyerowitz and Colin Westerbrook). So much of what calls itself street photography today (just Google the term, see what comes up) seems to be just people out walking along the street, doing whatever, without the mystical moments when everyone in the shot is arranged just perfectly (Winogrand’s benchful of folk at the 1964 World’s Fair), or caught at just the right angle (Frank’s elevator operator), or with just the perfect crazed expression (Klein’s alltime untoppable kid-with-a-toy-gun shot). Don’t get me wrong, there’s no reason street photography can’t still be vital, alarming, magical. It’s just that if it’s not those things, instead just photos taken on the street, then what’s the point?

Which leads to Anders Petersen, still busy out there around the world and still taking shots only he can. His latest book, Okinawa, is actually comprised of photos from 2000, when he was in that Japanese city for a three-week residence. It’s a slightly different photobook than his other recent city books such as Roma, frenchkiss, and Soho, not to mention Steidl’s three-part City Diary. The classic Petersen book, of course, is his first, Café Lehmitz, where he dives deep into Hamburg’s redlight district and comes out, well, not the Beatles, but with one of the classic works of lowlife excess. Café Lehmitz is all interior shots; the later city books blend interior and exterior shots. They’re also uniformly printed in intense high-contrast blacks and whites. (Too bad Petersen missed the gravure age; his books cry out for those meaty slabs of poisonous ink.)

What makes Okinawa a little different is that it’s all exterior shots, a number taken on a beach (I haven’t found a grain of sand in Petersen’s other work), and that the printing is more muted, with a brown-gray tone rather than stark blacks and whites. It’s also a slightly quieter book, with less of the in-your-face personalities resplendent throughout his other work. If the crazy drunk antics of the Café Lehmitz set a tone of behavior often captured by Petersen in his other books (women smoking cigarettes with their toes, men with six-inch scars on their cheeks, couples copulating in cramped rooms, oysters acting up), well, Okinawa is downright tame. The wildest we get is a schoolgirl inexplicably flashing her nipple while two friends look away indifferently.

Otherwise, we find in the book basically what a brilliant photographer comes up with during three weeks spent walking around with his camera in a place halfway around the world, i.e., what turns up in front of him, and which he’s fast or when speaking with a stranger, charming enough to catch. So we get a lot more almost conventional street shots than are in books such as Roma and Frenchkiss. Petersen, known for tight focus, getting right in his subjects’ faces, here in Okinawa stands back, puts people in their environment: a hatted man with flowers on a park bench; a family settling into their beach chairs on the sand; six people in a sidewalk shot, one a boy in his father’s arms, dozing on his shoulder. Want strange in Okinawa? Well, there is a guy walking by with a ten-foot-long stuffed dolphin on his shoulders, which is …

Well, not very kinky, but still all Anders Petersen. And resplendent with the gift a great photobook maker has. Each photograph on its own might not be amazing, but they all add up to a strong book. As Paul McCartney said to criticism of the Beatles White Album (fifty years old now!), “Hey, it’s the bloody Beatles White Album.” Sure, it might have a “Why Don’t We Do It in the Road” or a “Honey Pie,” but as a complete album it’s timeless.

I’m not sure Okinawa is quite a timeless book, but it’s a worthy addition to Petersen’s body of work, and also an example of an intriguing photographic challenge: How do you make a book in three weeks halfway around the world in a place you can (I’m drawing on my own experience here) barely understand.

If you read my recent three-part Japan Journal for Photobookstore Magazine, you know I recently faced the same challenge: How to make a photobook of a city (Tokyo) in which I spent most of my time trying not to get lost on the streets and subway. Well, I did what I always do, wherever I am. I put my head into the place where I see everything around me as intensely as possible, constantly looking for photos, then take my camera and do my best to capture them. (My two Japan books, “Shibuya Time” and “Lost in Tokyo,” will be out soon.)

In an afterword, Petersen talks about how he tackled Okinawa (city and book): “My timetable was short. I made a choice and dived into the diversities of the streets, the presence and the living energy, no matter what it was. It’s about the desire to be surprised by the unpredictable, and the magic of innocence. And it has always been the wish to get closer to other people and learning something, that’s what counts.”

The presence and the living energy. I couldn’t put it better. That’s what we want in, well, if not what’s tiresomely still called street photography, how about in photographs taken out on “the diversities of the streets.” It’s capturing human force and weakness, disparate and rich personalities, inexplicable happenstance, and the essential magic lurking within daily life that’s always made photographs on the street worth celebrating.

And we can still do it, as long as a photographer with true vision and originality is behind the lens. As Petersen also writes, “The authenticity of documentary photography is punctured since long ago. It refers only to the author.”

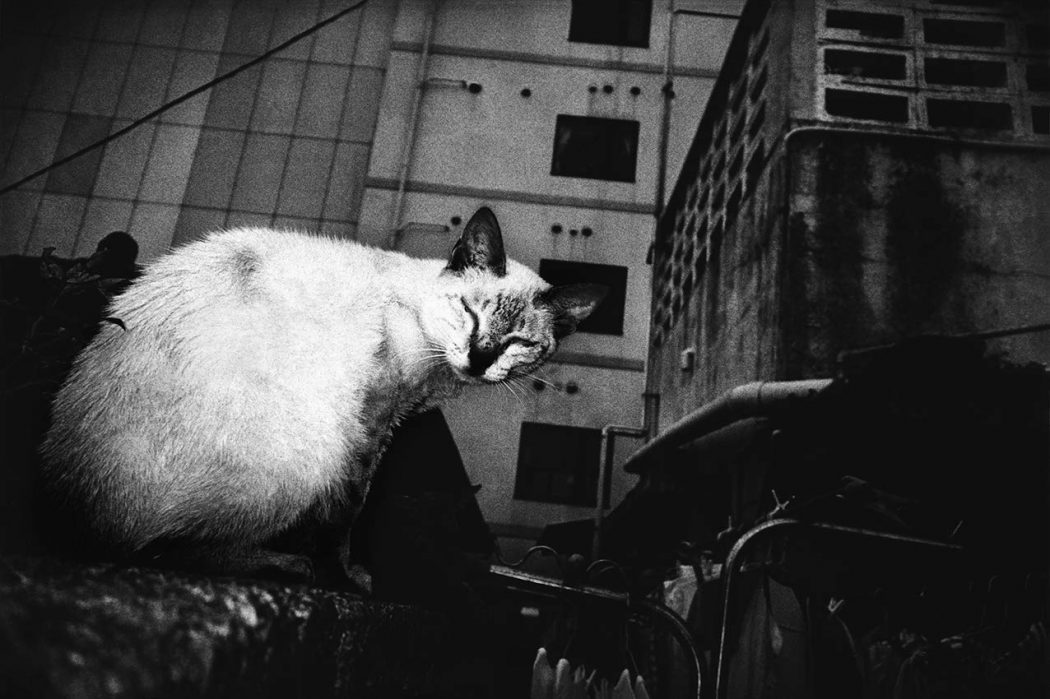

Yes, yes, yes. That’s exactly what we want: the author present in every shot taken, every choice of photo for the book, the order of the photos, the way the book reads to us. (And if there’s any doubt that the author is present, in the second photo we get one of Petersen’s trademark stark-eyed, feral cats, though in Okinawa it’s only a small part of a photo of an outdoor cigarette machine.) There is nothing dead about street photography when it’s written by a true author, a true artist.

So check out what Petersen could do in three weeks far, far from home. Pick up Okinawa. Then after enjoying his presence-rich street photographs, do as I’ve been doing for the last few days: try to make sense of some of the koans he drops into his afterword:

“I am primitive and need to be touching distance to know I exist.”

“When shooting I want to know, but I’m unsure if I always want to understand.”

“Looking at the colorful life in front of me, exposed to the exposed ones.”

“Photography has never been innocent.”

“I learned that photography is not about photography. And being strong is not going to help you much. But being weak opens up the presence.”

Think about that last sentence in particular. That’s what anyone heading out on the streets to take photos has to keep in mind. You’re there for one simple reason: to open up the presence.

And, boy, does Anders Petersen do it in every book he puts out.

Okinawa by Anders Petersen can be purchased here.

Robert Dunn is a writer, photographer, and teacher. His latest novel is Savage Joy, inspired by his first years in NYC and working at The New Yorker magazine. His photobooks OWS, Angel Parade, Carnival of Souls, and New York Street are in the permanent collection of the libraries of the Museum of Modern Art and the International Center of Photograph (more info on Dunn’s own photobooks here; prints of his work can be ordered here, follow his instagram here). Dunn also teaches a course called “Writing the Photobook” at the New School University in New York City.

1 Comment