It’s a small, unpretentious book; minuscule. In fact it’s smaller than the A5 notepad I’m using to write this. It can’t be overstated how under-appreciated small books are – a big, flashy, expensively produced book isn’t going to compensate for poor quality work and the vice versa. Self-Portraits by Yurie Nagashima can be held in one hand and this simple fact feels great. The book includes a conversation with Lesley A. Martin, Aperture’s creative director and I will go against the purists here, those claiming that a photo book ought not to contain any text because the pictures should be able to speak for themselves. Be that as it may, the written piece provides context and it’s convenient to have photographs and text in the same place. It’s an enlightening piece which mentions Nagashima’s other creative outlet, writing, and her general attitude towards art and language. Similar to Victor Burgin, who claims that language plays a role even in the uncaptioned photograph the moment it is looked at, she doesn’t believe that art can live without language. It also discusses her thoughts on femininity, self-portraiture and education, how when a woman makes a self-portrait she is “taking action against the historical roles of the male and female in photography”.

There is a tendency in photography when (rightly so) considered as art to be expected to mean something deeper, much bigger than what’s on the surface. This is absolutely right and proper, but there is also the opposite trend – unless your photographs mean something much deeper and generally different or invisible from what’s instantly accessible from the pictures they are not worth one’s time. I profoundly disagree. Self-Portraits presents what you see on the surface and a bit more too.

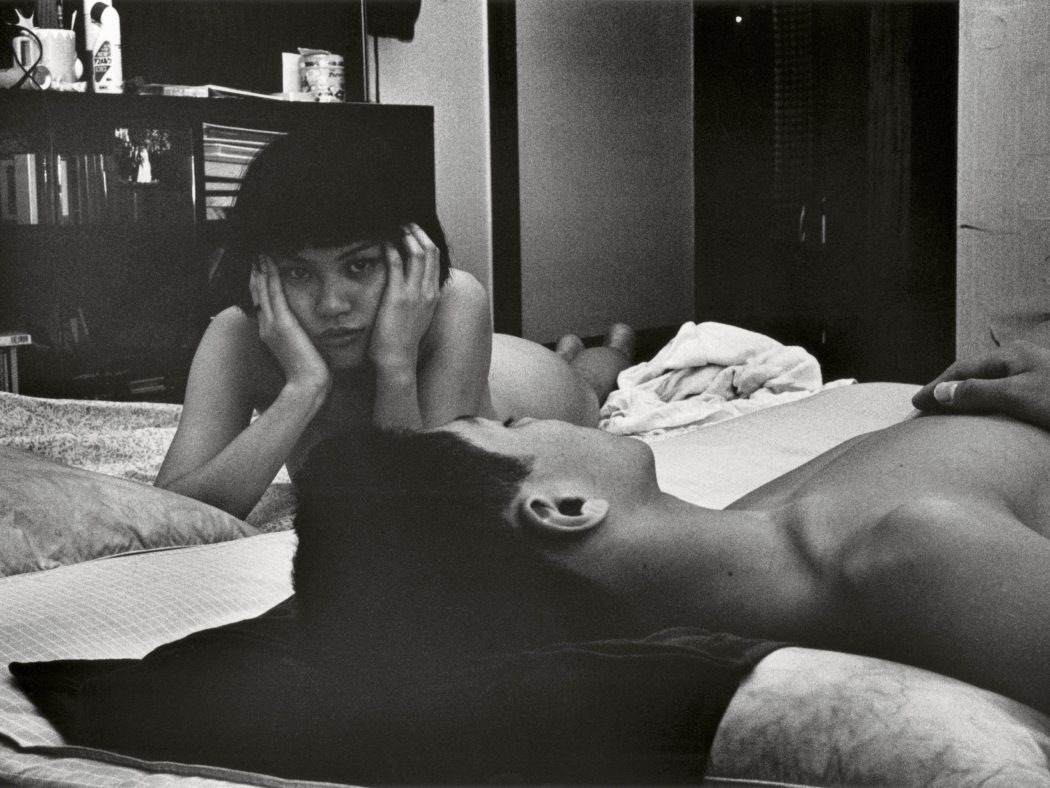

The book itself is fantastic – I wouldn’t call it grand, great or gorgeous but it’s perfect for its content. The title is simple enough not to need decoding. I miss the simplicity and openness in photography – nowadays more often than not I struggle to connect title and content, which is not necessarily a bad thing as it opens up many different doors of meanings and possibilities, but the opposite shouldn’t be easily dismissed either. Self-Portraits is the perfect example of the power of photography when a myriad pictures are sewn together to form a coherent project. Most of the photographs are unexceptional in their own right and I’m not saying this in a disparaging way – they wouldn’t merit from being enlarged and put behind glass in an expensive frame, this is just not the strength in this body of work. The book is the perfect form as it preserves the intimacy of the subject matter. The pictures are arranged chronologically which certainly works as they were taken over a substantial period of time and this allows the viewer to see the life of the author unfold, from the care-free performative days of casual backpacking and leisurely sexual encounters up to becoming a mother and learning what that entails on the go. The portraits in the book are markedly different in their form and function than selfies on social media. There’s no gloss or glamour and the message isn’t “look at me, my life is amazing and I’m beautiful”. Self portraits have quite an important role to play when performed by a woman as they subvert the power dynamic between a (usually) male photographer and a (usually) female model. They eliminate the power play, the notion of somebody taking advantage and treating the other as a prop and give the model (who is also the picture-taker) full control instead.

Grainy black and white nipples, bondage, pulled down knickers, the camera hugely prevalent in the filthy mirror, shaved head, piercings and fag in mouth, naked bums, exposed vaginas, smoking even more, blood dripping between feet; once Nagashima becomes pregnant and gives birth to her son, around half way through the book, the images take an abrupt turn. Suddenly this little person enters her world and it becomes all about him – he’s in almost every picture – and Nagashima’s relationship with him. The nudity disappears almost entirely, save for a nipple here and there – the difference is striking, it feels as if these are two different bodies of work about two different people. She transforms, as if overnight, into a doting, responsible mother, a woman one would expect to see in a high-flying corporate job. Is it all intentional and performing for the camera? One can’t help but think of Amalia Ulman, Cindy Sherman and Juno Calypso who all act for the camera very much aware of its power to transform. The last picture before the baby appears is of Nagashima, heavily pregnant, in her underwear and leather jacket, no bra, cigarette in mouth, a slight pout and giving the finger. Who is she showing her middle finger to? The father, who is neither seen nor even hinted at, as if he’s unimportant perhaps? Or maybe patriarchy which dictates that women can’t take responsibility for their own bodies and life choices. Her world has rapidly changed and the viewer takes part in sharing the experience.

Life is a confusing, debilitating and incredibly uncertain journey. As the saying goes, it only makes sense when looking back, only then can one connect the dots and it all clicks. One of the most common reactions when looking at one’s self portraits, especially if they are from years ago, must be “I can’t believe I was wearing this” or “why did my hair look like that”, yet it’s one of the most important tools of remembrance we have now as change happens gradually and before we know it it’s already occurred. Self-Portraits is poignant, full of twists and turns but also humble and quiet in its presentation. Quiet and inconspicuous in the form of a pocket-sized book, yet the pictures scream in the face of all who don’t see women as equal to men. It claims and demonstrates how demonically outdated and wrong these beliefs are – here is this young woman drinking, smoking, having fun and enjoying life to its fullest with, bar a few exceptions like a lover in the very beginning and her son towards the end, no men.

Self-Portraits by Yurie Nagashima can be purchased here

Zak Dimitrov is a photographic artist, lecturer and writer. He received an MA from the University of Westminster and BA (Hons) from The Arts University Bournemouth. Zak’s work deals with memory, the passage of time, mortality and the physicality of photographic materials. He is the Associate Editor at American Suburb X.